|

|

|

|

|

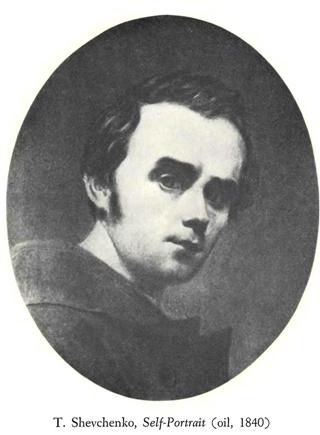

Taras Shevchenko,

"Self-portrait, 1861"His final weeks, when he was almost completely bed-ridden, were occupied with plans for distributing his Bukvar and for arranging for the proceeds from its sales to be transmitted for the support of Sunday schools which were then being established in the villages for the general education of both children and adults. Even on his death bed he was still dreaming of a cottage overlooking the Dnieper, and sent instructions to Vartolomiy to forget the sites then under consideration and to try to buy him a patch of land on an elevated location near the town of Kaniv, as if he had foreseen that that would be his final resting place. In his last poem, written with a trembling hand two weeks before his death, he addressed his Muse and prepared for the long journey with her to the nether world where, on the banks of the Styx he would finally build himself a dwelling and live there with her as his wife. His earthly course almost over, there remained nothing for him but to suffer and wait for the inevitable end, which came on February 26, 1861, one day after his forty-seventh birthday. He would have been overjoyed, if he had lived a week longer, to hear the proclamation announcing the abolition of serfdom in the Russian Empire.

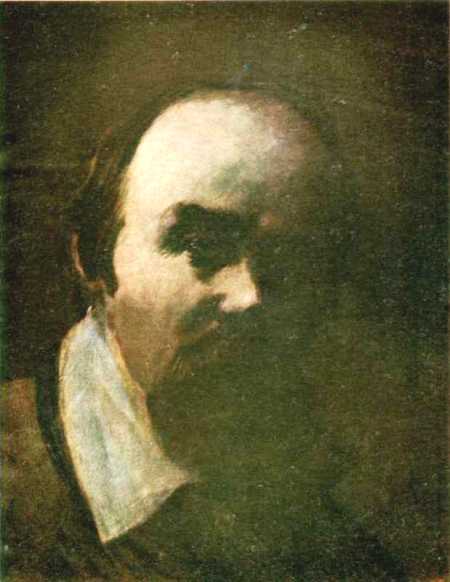

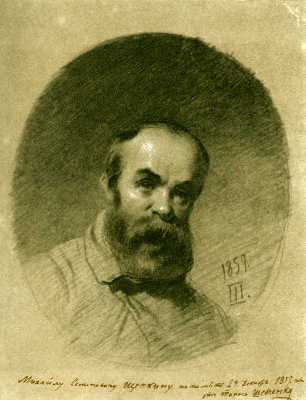

Taras Shevchenko,

Taras Shevchenko,

"Self-portrait, 1859"

In June 1859, he again found himself on Ukrainian soil, visiting the villages where he was born and brought up and spending leisurely days at the homes and estates of his friends scattered about the province of Kiev. Particularly tender was his meeting with his sister Yarina in the village of Kirilivka and with his sister-in-law’s brother, Vartolomiy, a steward on the estate of a Ukrainian landlord in the vicinity of Korsun.

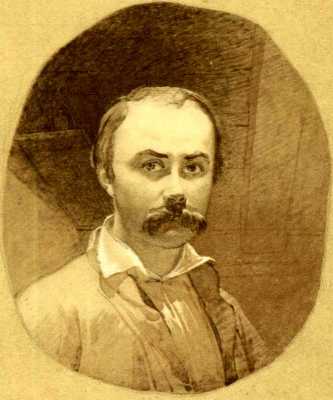

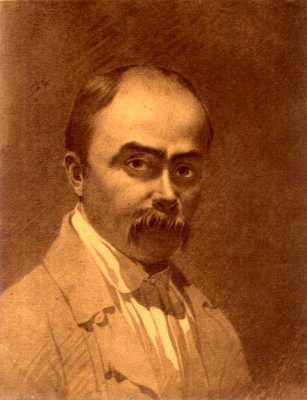

Taras Shevchenko,

Taras Shevchenko,

"Self-portrait,1858"Having returned to St. Petersburg, his first visits were to his closest friends, M. Lazarevsky and the Tolstoys, who were more instrumental than anyone else in helping him regain his freedom. His arrival at the Russian capital was a social event of the first order, and he was wined, dined, and lionized even to surfeit. In addition, he plunged himself into the cultural and artistic life of that imperial city with as much gusto as if he wanted to make up in a few days for the lack of it he had experienced for ten years.

T. Shevchenko.

"Self-portrait.

Nizhny Novgorod,1857"Shevchenko was free again, and on August 2, in a fishing boat, he sailed across the Caspian to Astrakhan, which he reached three days later. On August 23, after nearly three weeks in that unattractive city, where he visited many of the friends he had known in Kiev, he sailed on a steamship up the Volga to Nizhni Novgorod. On the way he visited Saratov, Samara, and Kazan. When on September 20 he reached his destination, the police presented him with an order from Uskov to return to Orenburg, for, according to the latest official communication which Uskov received shortly after Shevchenko had left, the poet was not to return to St. Petersburg or to Moscow but was to wait in Orenburg for further instructions as to where he was to go. The difficulty was overcome by his friends in Nizhni Novgorod who advised him to simulate an illness.

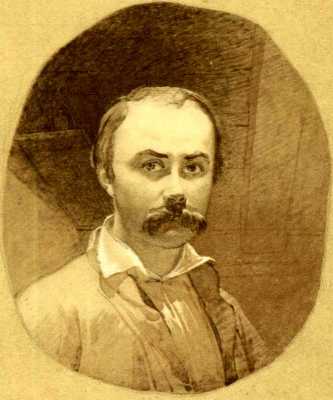

Taras Shevchenko,

"Self-portrait,1853"The worst period of his life had begun. He arrived there with a band of political "criminals" to whom all correspondence was forbidden. After two and a half years of freedom from military training, he was again subjected to it. He was placed under the supervision of a coarse, brow-beating captain, Potapov, who mocked, drilled, and disciplined him mercilessly and almost each day searched his pockets to see if he had written anything. But an even greater curse than this beastly creature was the bleak environment of sandy, marshy, rocky tracts. With the exception of the Bible, he had no books to read.

Taras Shevchenko,

"Self-portrait,1850"At that time Shevchenko lived at the home of Captain K. Gem, who was attached to the Governors suite. It was actually through the good offices of his host that the poet enjoyed the benevolence of the Governor. However, he was not one to let well enough alone. For some time he noticed that a certain lieutenant, M. Isayev, was paying intimate visits to Gern's wife. When the matter became clear to him beyond any shadow of doubt, Shevchenko, outraged at such an injury to his benefactor, brought Gern home to reveal to him the flagrant misdeed. To revenge himself on the delator, the very next day Isayev reported to Governor Obruchev that Shevchenko, contrary to the prohibition, wore civilian clothes, lived outside the military quarters, wrote verses, and painted. All that was perfectly well known to Obruchev, but, although he would have preferred to let the matter rest there, now that it was made public, he dared not for fear that Isayev might report on his lenience to the authorities at St. Petersburg. He therefore ordered a search of Shevchenko's apartment.

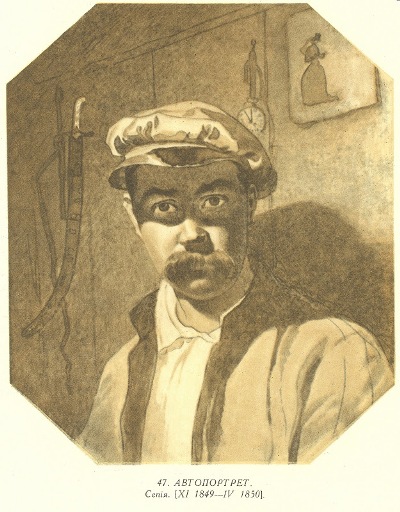

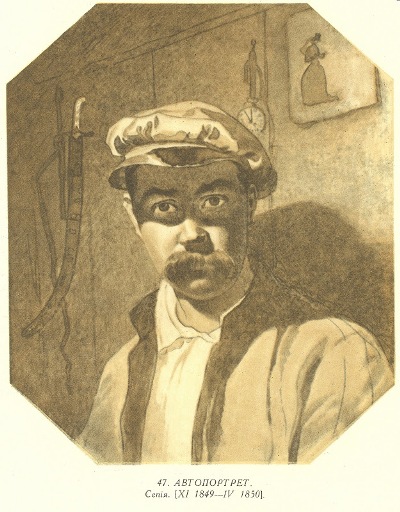

Taras Shevchenko.

"Self-portrait, 1849"In the spring of 1848, the government organized an expedition under Captain O. Butakov to study the as yet unexplored Aral Sea, its depths and coastline, writh a view to the advisability of building fortifications upon its shores for further imperialist expansion in the direction of Afghanistan. The expedition needed an experienced draughtsman to sketch the salient places where fortresses might be constructed. And so, at Butakov's instance and after investigating Shevchenko's behaviour, the military authorities at Orenburg decided to appoint him to that task, although no permission had as yet arrived from St. Petersburg to free him from the curtailment of drawing and painting. On May 9 Shevchenko received instructions from Orenburg that he was being relieved from the regiment at Orsk and attached to the expeditionary battalion, with the right to draw and sketch anything that was considered necessary. Although, according to those who had lived in the Aral region, life at Orsk was an Eden in comparison, Shevchenko felt a sense of relief. The next day he was on the way to his new destination.

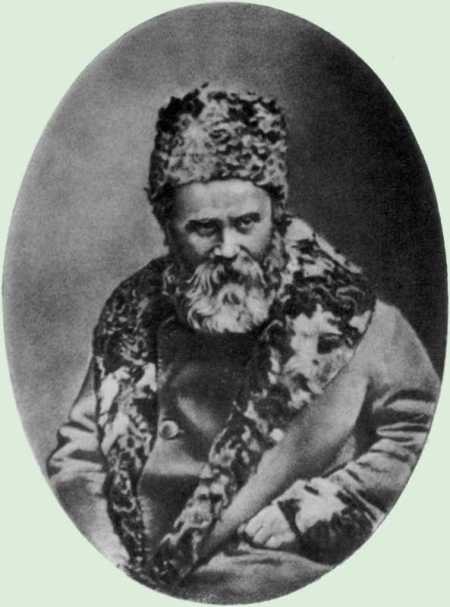

Kornylo Ustyianovych,

"Shevchenko in Exile

(early 1890s)"To relieve his plight, Shevchenko's friends helped him as much as they could with books, money, and other gifts. Of particular satisfaction to the poet was the receipt of Shakespeare's translated works and an entire painting gear. The Bible continued to be his constant companion, and from it he drew what consolation he needed. While in the Fortress of Orsk, Shevchenko experienced the soothing power of prayer and felt alleviation on meditating Christ's call: “Come to me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden and I will give you rest.” I his he confessed in some of the letters to his friends. Of great balm to kim also was Thomas a Kempis's Imitation of Christ. Although strictly forbidden to write, Shevchenko nevertheless found surreptitious occasions to do so, especially when all in the barracks were asleep; but, as he relates in his “To A. Y. Kozachkovsky,” it was “like a thief” that he went about it. Whatever he wrote he recopied in minuscule script and hid it in the leggings of his military boots.

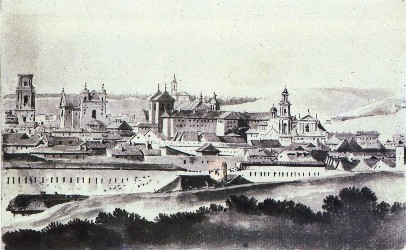

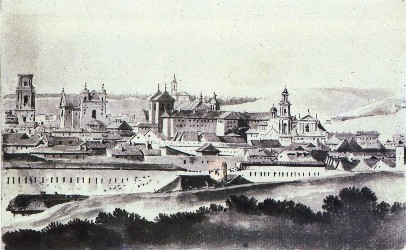

Taras Shevchenko.

"Catholic church in Kyiv"Shevchenko was arrested on the Kiev bank of the Dnieper (on April 5, 1847) as he stepped down on dry land from a ferry. In his baggage the police found, in addition to paintings and sketches, a number of personal letters considered subversive in character and, above all, a copy of the manuscript “The Three Years,” containing the already mentioned illegal and incriminatory poems. All this evidence was sent to St. Petersburg. After spending one night in a Kiev prison, Shevchenko was transported under police escort to the Russian capital, which he reached eleven days later. His comrades in the accusation had been imprisoned there several days earlier, Kulish having been arrested while actually on his way abroad to continue his studies in preparation for a professorship.

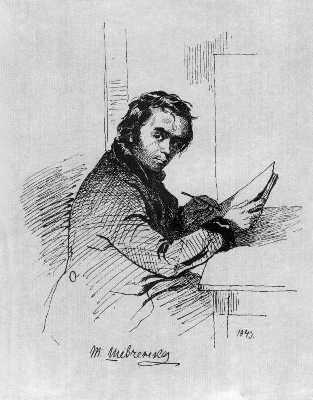

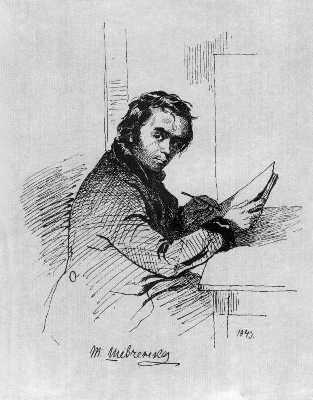

Taras Shevchenko,

"Self-portrait, Yagotin,

1843"In this period of his life, marked by his chief political poems written since 1843, and by the furtherance of the ideals expressed in them, Taras Shevchenko from a mere national bard assumed the stature of a national oracle, a seer of his country's future, a luminary of the first magnitude whose like Ukraine had never seen before. Occasionally he would meet Kostomariv and the other Brothers at the apartment of M. Hulak, where they discussed matters pertaining to the Slavic world. Little did they suspect that one O. Petrov, a student and a spy, was listening to their arguments behind the thin partition separating Hulak's and Petrov's living quarters. It was this student who kept the Russian authorities informed of the activities of the organization and whose final testimony led to the arrest of its adherents.

Taras Shevchenko,

"Blind woman with daughter.

After the motive of the

"Blind woman" poem"Shortly before his emancipation, and particularly directly following it, Shevchenko's predominance as a poet became quite marked, in spite of his continued cultivation of a career in painting. He began as a strict romanticist with the ballad “The Bewitched Woman" (Przchinna') which he wrote in 1837. The next year proved prolific in shorter lyrics and longer poems, twelve items in all, written under the influence of the social conditions either of his day or of the Cossack historical past. The encouragement and impetus to their publication was supplied by P. Martos, a wealthy Ukrainian landlord from the Poltava region, whose portrait Shevchenko was painting at that time.

Taras Shevchenko,

"Cossack feast", 1838One acquaintance led to another, and in time Shevchenko became known to many influential people in artistic circles, including the Ukrainian-born, Dmytro Hrihorovich, the secretary of the board of the Academy of Art; Oleksij Venetsianov, the painter; Karl Briullov, the creator of “The Last Day of Pompeii" canvas; and the famous Russian Romantic poet, Vasyl Zhukovsky, the tutor of Tsarevich Alexander. By that time Shevchenko had produced several paintings dealing with old Slavic and Classical themes, and these revealed him to them as an artist of some promise. Among this coterie it then became a question of freeing Shevchenko from serfdom; and it was finally decided that Briullov would paint a portrait of Zhukovsky that would be auctioned off at the imperial court for at least 2,500 rubles, the sum demanded by Engelhardt for Shevchenko's liberation.

Vilnius city panorama,1785

Painted by Franciszek

SmuglewiczPresently the fourteen-year-old Taras was taken into the palace in the nearby town Vilshana to serve as a helper to the cook, but, failing in the kitchen, he was transferred to the apartments to attend his lord as a lackey. However, he was not to be pinned down to drudgery, and whenever he could he would escape to pass his time secretly in musings, drawing, and painting, especially at night when he could not be detected. Once, however, he was surprised by the lord at sketching and was mercilessly beaten for running the risk of setting the house on fire by burning the midnight oil. The next day he was soundly birched to boot. This happened in Vilna, where P. Engelhardt was living, together with his suite, as an adjutant to the Russian governor of the province of Lithuania. However painful the incident may have been, it marked a turning point in the budding artist's life, for it finally dawned on the master that his footman was talented indeed and warranted lessons from a competent teacher. And so in 1830 began his formal art studies at the studio of Jan Rustan of Vilna.

He was barely nine when his mother died at the age of thirty-seven. A few months later his father married a widow, Oksana Tereshchenko, who brought into his household three children of her own. The fostermother was a termagant not only to her husband but also to his children, particularly to young Taras, whose stubbornness irritated her greatly. To prevent as much as he could her harsh treatment of his son, the father would often take him on his carting journeys. During one of those expeditions the older Shevchenko caught a severe chill and shortly after his return home died in the early part of 1825, aged forty-seven, when Taras was about eleven. Life with the fostermother then became doubly intolerable, and many a time he had to seek protection from her by escaping to his eldest sister, who was by that time married and living apart. He was barely nine when his mother died at the age of thirty-seven. A few months later his father married a widow, Oksana Tereshchenko, who brought into his household three children of her own. The fostermother was a termagant not only to her husband but also to his children, particularly to young Taras, whose stubbornness irritated her greatly. To prevent as much as he could her harsh treatment of his son, the father would often take him on his carting journeys. During one of those expeditions the older Shevchenko caught a severe chill and shortly after his return home died in the early part of 1825, aged forty-seven, when Taras was about eleven. Life with the fostermother then became doubly intolerable, and many a time he had to seek protection from her by escaping to his eldest sister, who was by that time married and living apart.

Споріднені публікації, за тегами:

|

|

|

|

|

|

He was barely nine when his mother died at the age of thirty-seven. A few months later his father married a widow, Oksana Tereshchenko, who brought into his household three children of her own. The fostermother was a termagant not only to her husband but also to his children, particularly to young Taras, whose stubbornness irritated her greatly. To prevent as much as he could her harsh treatment of his son, the father would often take him on his carting journeys. During one of those expeditions the older Shevchenko caught a severe chill and shortly after his return home died in the early part of 1825, aged forty-seven, when Taras was about eleven. Life with the fostermother then became doubly intolerable, and many a time he had to seek protection from her by escaping to his eldest sister, who was by that time married and living apart.

He was barely nine when his mother died at the age of thirty-seven. A few months later his father married a widow, Oksana Tereshchenko, who brought into his household three children of her own. The fostermother was a termagant not only to her husband but also to his children, particularly to young Taras, whose stubbornness irritated her greatly. To prevent as much as he could her harsh treatment of his son, the father would often take him on his carting journeys. During one of those expeditions the older Shevchenko caught a severe chill and shortly after his return home died in the early part of 1825, aged forty-seven, when Taras was about eleven. Life with the fostermother then became doubly intolerable, and many a time he had to seek protection from her by escaping to his eldest sister, who was by that time married and living apart.