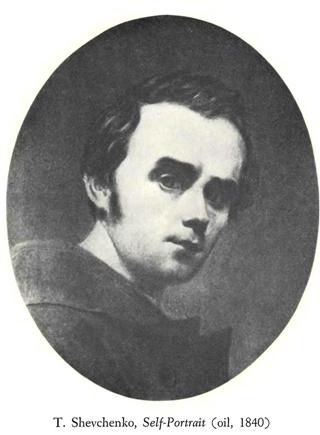

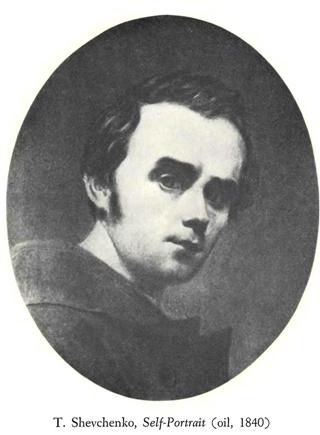

TARAS SHEVCHENKO’S LIFE AND WORK

Shevchenko in exile at Novopetrovsky Fort (part of Taras Shevchenko biography, by C.H. Andrusyshen)

(Introduction of "The poetical works of Taras Shevchenko. The Kobzar" by Constantine Henry Andrusyshen and Watson Kirkconnell)

Tsar Nicholas, on Orlov's advice, again refused to remove the ban and, in addition, ordered that Shevchenko be transferred to another, more distant fort to continue serving his sentence. And so, after two and a half months' imprisonment at Orsk, on October 8 Shevchenko was taken to the relatively recently established Fortress of Novopetrovsk situated on a peninsula of the Caspian Sea. Sailing down the Ural River and then across the Caspian, he was brought there on October 17, 1850.

Taras Shevchenko, "Bay near Novopetrovsk fort"

The worst period of his life had begun. He arrived there with a band of political 'criminals" to whom all correspondence was forbidden. After two and a half years of freedom from military training, he was again subjected to it. He was placed under the supervision of a coarse, brow-beating captain, Potapov, who mocked, drilled, and disciplined him mercilessly and almost each day searched his pockets to see if he had written anything. But an even greater curse than this beastly creature was the bleak environment of sandy, marshy, rocky tracts. With the exception of the Bible, he had no books to read. It was therefore with great relief that Shevchenko welcomed the arrival of an expedition whose purpose was to explore the deposits of hard coal in the Kara-Tau Mountains.

Taras Shevchenko, "Rock "Mon"

Shevchenko was assigned to that expedition in a military capacity, for hard labour, but its leader allowed him to sketch whatever was of interest in that mountainous domain of wild birds and beasts of prey. Upon his return, two months later, these sketches were entrusted to his friends, and it was only later, with the amelioration of his circumstances, that he could, at leisure, bring them out as finished compositions.(1)

Towards the end of 1852 came a change for the better. His drillmaster Potapov was transferred, and the new officer, Captain Kosarev, was not as hard on the artist. To replace the commander of the Fort, Mayevsky, who treated Shevchenko humanely, came Major I. Uskov, who was prevailed upon by the poet's friends at Orenburg to make life easier for him, which the officer did, although he could not relieve him from daily muster or permit him to use his brush. Yet he could not forbid him to occupy himself with sculpture, mostly bas-reliefs, as that was not mentioned in the sentence.

.jpg)

Taras Shevchenko, "Bay near Novopetrovsk fort"

Likewise at that time Shevchenko began to write novels in Russian, the first one entitled The Servant Maid (Naymichka), which, in order to avoid unpleasantness, he dated back to Pereyaslav, 1845. At this he was engaged fairly regularly, and before his days of exile were over he had completed seven novels. In addition, he did not neglect his Diary. However, not a single original poem in Ukrainian was written by him during his seven and a half years at Novopetrovsk; and it seemed that his Muse, like his friends in Ukraine, had deserted him completely. But he continued to paint surreptitiously, and for some of his works, mostly portraits, which he sent to Orenburg as "cloth material," he occasionally received money. Thus did he while away his time and melancholy, and avoid being completely submerged in despair. On rare occasions he was visited by people travelling through that outlandish place, among them the famous Russian novelist, O. Pissemsky, who was always favourably disposed towards him.

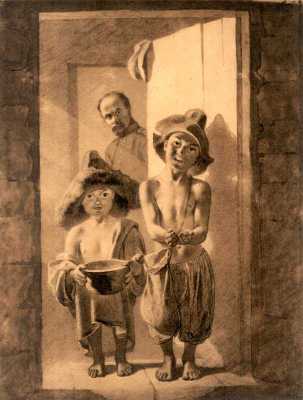

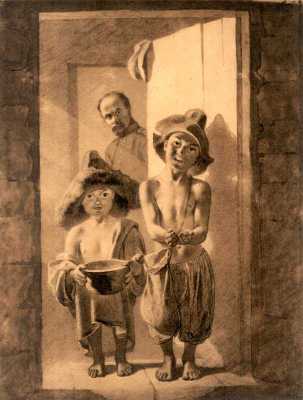

Taras Shevchenko. "Baygush"The greatest consolation Shevchenko experienced in that gloomy period of his life was in the person of Uskov’s wife Agatha, whom in his letters to his friends he described as “the veritable grace of God" to him in that wilderness. To Bronislaw Zaleski, his Polish friend, he confided: “What a wonderful, marvellous being is that impeccable woman! She is a sparkling gem in the crown of creation. If it were not for this one and only creature so dear to my heart, I would not know what to do with myself. I have come to love her with a chaste, lofty love - with all my heart and soul filled with gratitude. But do not suspect, my friend, that there is any taint in this pure love of mine... And indeed, it was a platonic affection which Agatha, feeling how it relieved his torment, allowed him to nurture towards her. Almost every day he dined at the Uskovs, and his frequent walks with her in the vicinity of the Fort transported him from hell to the empyrean heights, preventing him from going mad among the uncouth, obtuse, drunken soldiery and convict rabble with whom he had to live.

The death of Nicholas I occurred in February 1855, and immediately Shevchenko saw a ray of hope for himself even so far as regaining his complete freedom. In April of that year he wrote a diplomatically worded letter to the Vice President of the Academy of Art, Count F. Tolstoy, and to his close friend V. Hrihorovich, its Secretary, to petition the sister of the late Tsar, Maria, then the President of the Academy, to help relieve his predicament. Two months later he received an anonymous letter, written probably by Countess Tolstoy, which offered him some assurance that in the near future his hopes might materialize. With the accession to the rone of Tsar Alexander II, an amnesty for political prisoners was proclaimed. The new ruler, however, did not show this favour to Shevchenko, perhaps being influenced by his mother, in whom the poet's insult ("The Dream") still rankled deeply. He was refused not only a pardon, but also a commission for which he had applied. His bitterness was increased when Agatha Uskov, fearing scandal as a result of his frequent visits and their familiar promenades, broke off her friendship with him and began to treat him coldly. To Shevchenko, who considered her as his only mainstay in life, this was the hardest blow of all those he had experienced in the past eight years, during which his despair often reached such proportions that he was on the point of losing his bearings and sought to drown his sorrow in liquor. Although he certainly did not become an addict, in the last two years of his exile his consumption of alcohol showed a marked increase. It was this proneness, more than anything else, that apparently contributed to Madame Uskovs decision to sever relations with him.

(1) As a pictorial artist Shevchenko cannot be considered of the first rank. However, in his prolific production he did create many works of sterling worth. According to Professor V. O. Buyniak’s computation, some 835 items can be credited to him, mostly pen or pencil sketches and drawings (356), water colours and sepias (176). He was quite in demand as a portraitist (and in that respect he often excelled), but it was as an engraver that he was chiefly recognized by the Academy of Art.

Introduction written by Professor C.H. Andrusyshen

Source: The Poetical Works of Taras Shevchenko. The Kobzar. Translated from the Ukrainian by С.H. Andrusyshen and Watson Kirkconnell. Published for the Ukrainian Canadian Committee by University of Toronto Press, 1964. Toronto and Buffalo. Printed in Canada, Reprinted, 1977, p.33 - 36.

Read more:

Introduction of "The poetical works of Taras Shevchenko. The Kobzar" by Constantine Henry Andrusyshen and Watson Kirkconnell.

.jpg)