|

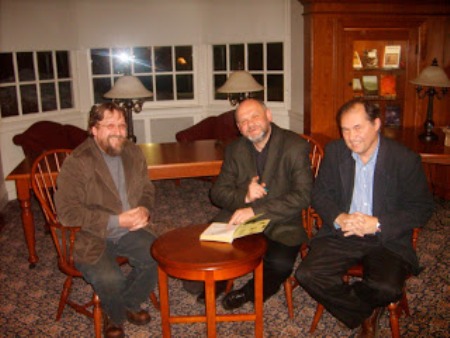

Interview with a Translator: Michael Naydan

- I began to translate when I was a student at The American University in Washington, DC. Back then I was taking Russian courses for my undergraduate major and my professors (among them Vera Borkovec from Czechoslovakia) gave me assignments to translate various Russian poems. I also read the great Russian poets in my classes with Professor Boris Filippov, who was extremely supportive of my career as a scholar and translator. I also took creative writing classes with two very talented poets, Henry Taylor and Myra Sklarew, who particularly appreciated poetry in translation. At that time I began to translate Anna Akhmatova, Alexander Blok, Osip Mandelstam, Boris Pasternak, and others. My first published translations appeared in the literary journal Hyperion in 1976. I began working on Ukrainian translations when I was in graduate school at Columbia University. While at Columbia, I won an award for best translations of Russian poets into English three times. Professor Robert Maguire particularly supported my work in the area of translation. He himself was a translator of Polish poetry as well as the Russian writers Andrei Bely and Gogol. And Professor John Malmstad insisted that students translate the poems we analyzed in his Russian poetry seminars to get a better understanding of the poetry. He suggested that I translate Marina Tsvetaeva’s collection After Russia in the process of writing my dissertation. I eventually published my translation of that collection as a book with Ardis Publishers. The poet and translator Bohdan Boychuk, the poet Vasyl Barka, and the scholars Assya Humesky and John Fizer all were very supportive of my early work on Ukrainian authors. At that time very few people were working on translating Ukrainian literature into English and Professor George Luckyj from the University of Toronto had stopped translating close to his retirement. It was then that I decided to translate from Ukrainian with more of a sense of purpose. My first book, translations of the poetry of Lina Kostenko, came out in 1990 with Garland Publishers in New York City. Professor Fizer particularly supported the translation of my first book and gave me a great amount of encouragement. - From which languages do you translate? And how is it that you've selected these languages in particular? - I translate from Ukrainian, Russian and Romanian. The Russian language is my main area of specialty, Ukrainian – the native language of my parents. I began to translate from Romanian thanks to my acquaintance with the Romanian poet Liliana Ursu, who came to my university (The Pennsylvania State University) two times on a Fulbright fellowship. - Tell me a little about how you approach your work, translating a novel, a collection of stories, a collection of poetry. What is in common? What stands out? What steps do you usually take in the process of translation? - I always try to keep close to meaning of the text in the original while making the translation readable in English. This is always a balancing act. Translation of poetry makes you focus more on hearing the voice of the poet and on the poem’s sound. In poetry translation you need to maintain the sound structure (the sound quintessence) of the original, and also what I often call the organic rhythm. For example, the essence of Natalka Bilotserkivets' poem "The Saxophonist" cannot be translated without its sound patterning. I tried to convey that in my translation. On the other hand, prose demands a more logical approach, although you often come across poetic prose in the works of writers such as Yuri Andrukhovych. Poetry, of course, also has an inner logic, but they are other elements such as metaphor, syntax, rhythm, rhyme, etc. that play a more significant role. Usually when I am translating, I do a quick first draft either on paper, or typed right into the computer. When I translate poems, I often read the original out loud in order to better hear the melody and get myself into the world of the poetry. Sometimes I accidentally even learn poems by heart that way before I translate them. Then I set my translation aside for a while to maintain a certain distance, and then come back to work on nuances from time to time. Sometimes I send my translations to friends and colleagues to check them or to see how they work in English. In translating from Russian, I’ve worked together closely with my colleague from Bucknell University Slava Yastremski, who is a native speaker of Russian. We've team-translated Marina Tsvetaeva, Igor Klekh, Olga Sedakova, and a number of other authors. In fact, we are currently working on a translation of the first edition of Taras Bulba that was published in 1835. The Western world is largely unaware of Gogol’s first edition of the novella. Two heads with four eyes and four ears catch a lot more than just one head. In fact, Slava and I have been collaborating quite harmoniously on translations for quite a long time, over 25 years. When I translate from Ukrainian, I work together with various experts. It has been particularly great for me to work with Olha Luchuk. She and I have done the anthology of 20th century Ukrainian poetry 100 Years of Youth for Litopys Publishers and also The Flying Head of Viktor Neborak for Sribne Slovo Publishers. Olha works very meticulously and knows both languages extremely well, as well as the two extremely varied literary traditions. Most recently my former graduate student Olha Tytarenko has also assisted me considerably with my translations of Bohdan Ihor Antonycyh, Tanya Malarchuk and Maria Matios. Oksana Tatsyak has assisted me with my translations of Yuri Vynnychuk in the past. I am always grateful for collaboration with such incredibly talented and good people. All of them, in fact, are from the city of Lviv, which I have come to know as my home away from home. I'm also particularly grateful to Myroslava Prykhoda from Litopys Publishers, where Michael Komarnytsky is the director and where I publish quite a bit, for her meticulous editorial work on all my bilingual editions. - How do you get translation work? Do publishers contact you? How does this process usually happen? - It happens in various ways. Mostly, I decide on my own what I want to translate, or my colleague Slava brings something worthy of translating to my attention, and then propose the project to a publisher. You usually have to have either a completed project or a large part of a manuscript ready to show publishers. I need to be particularly enamored of a work in order to translate it. When I first read Yuri Andrukhovych’s novel Perverzion, I knew from the very first pages that I needed to translate it and contacted the author immediately for permission to work on it. I had earlier long been enamored of the poetry of Pavlo Tychyna, Lina Kostenko and Maksym Rylsky, so I did books of translations of each of those particular authors. Most recently I’ve done two books of translations of the poetry of Bohdan Ihor Antonych on the 100-year anniversary of his birth. Sometimes publishers, literary agents or the authors themselves contact me about doing translations. If a project interests me enough, I decide to take it on. For example, I was contacted by an editor (James Morrow) to translate a short story by Sergei Lukyanenko called “From Fate” for an anthology of European science fiction—and I agreed because the story was quite interesting. We changed the title in English to “Fate, Inc.” The same thing occurred with a story by Elena Arsenieva “Birch Tree, White Fox,” that appeared in the same volume of science fiction. Most recently I was contacted to translate another of Lukyanenko’s works entitled “Foxtrot at High Noon” for an anthology of vampire stories edited by John Joseph Adams entitled By Blood We Live, which just appeared a few months ago. Among other well-known authors the volume includes stories by Stephen King and Anne Rice. Once I was approached to translate a second book of the poetry Lina Kostenko because she was being nominated for a Nobel Prize. I, of course, immediately agreed to do it for the Ukrainian cause and also because I value her poetry highly. A while ago when I was in graduate school, I was asked to translate a collection of Vasyl Stus’s poetry. I declined for one simple reason – at that stage of my career I wasn’t prepared to translate his dense and complex verse. I would feel much more confident to work on him now. - What attracts you most in the area of translation? What are its positives? Negatives? - First and foremost I should point out that I don’t consider translation work my only area of expertise. I’m not limited just to that field. I also write poetry, songs, prose (a novel Seven Signs of the Lion), scholarly articles, etc. I also paint a little. All of this for me comprises creative work, and it has attracted me my entire life from my teenage years on. Since I teach, my university (The Pennsylvania State University) considers my accomplishments in translation part of my scholarly work. I always write introductions to each of my books of translations, and also often include copious footnotes for readers. The problem (at least a little one) is that from the financial point of view, a translator of artistic works rarely can make enough money to make a living. But I have my university job that allows me to work on translations. A translator of artistic works usually does not do translations for monetary gain, but for his own satisfaction or for the greater cause of being a mediator between different cultures. - Does it make sense to ask questions of the author of a work that you are translating? - Absolutely. When an author is amenable to it, you need to take advantage of that and ask questions. I grew up in the non-Ukrainian diaspora in the United States and not in Ukraine. Certain realia of Ukraine were not accessible to me until I was able to travel to Ukraine myself. Certain authors are more than willing to answer my questions, but not all of them. Lina Kostenko, for example, would never answer any of my questions. She once said to me when I asked her a specific question about one of her poems, “You’re the translator. You figure it out.” She is well known as a woman with a particular character. Many authors are quite supportive. I can single out Yuri Andrukhovych the most for his lengthy answers to my questions in my work on his novel Perverzion where I had to delve both into linguistic issues as well as learn an incredible amount of information about the city of Venice. Yuri deserves a medal for his patience and attention to my questions. I feel I should at some point gather together our emails and publish a book, because you’ll find a translation and creative workshop in them. I should also add that almost all contemporary authors whom I translate are prepared to answer my questions with no questions asked. - What experience, what knowledge and what qualities are particularly important for a translator of artistic literature? - A translator definitely needs to read a lot. To have a love for the written word and for literature. Dictionaries are one thing. In my personal library I have all kinds of the most important dictionaries that a translator would need. In Ukrainian dictionaries published in the diaspora there is a lack of contemporary words, in Ukrainian dictionaries from Ukraine there is a lack of older and dialectal words (Western Ukrainian Galician words, for example). Dictionaries on the Internet such as multitran.ru and electronic ones such as Abbylingvo make things easier for a translator. They allow you to work much faster. Every translator needs to practice the craft, to develop taste and intuition. Intuition, grounded in practical experience, is most important. Theoreticians of translation for the most part do not translate, and because of that, their experience is limited. It is better not to be a slave of any kind of translation theories, but you need to work out your own principles and approaches to your work. A translator categorically needs to know the culture, history, literature, and vocabulary of the language from which he translates. At the same time, it is necessary to deeply understand those same elements in his native language and culture. However, languages and traditions do not always coincide. Thus one needs to know those disparate moments and figure out a way to translate or explain them for another culture. - Do you recall any of your translations that particularly strike you? And if so, please speak to that a little. - No translation is perfect or ever complete. It was great for me to work on Andrukhovych’s Perverzion, because there are so many interesting problems for the translator (both linguistic and cultural). I write about that a bit in my article “Translating a Novel’s Novelty: Yuri Andrukhovych’s Perverzion in English,” which appeared in the Yale Journal of Criticism. I get a great deal of satisfaction when poetry naturally occurs in my translations (this happens in several of my translations of Lina Kostenko, Vasyl Symonenko, Attyla Mohylny, and others). Sometimes you hit the mark, other times (perhaps most of the time) – you don’t. Once a literary scholar from the diaspora wrote to me that it’s impossible to translate Tychyna’s poetry and that I should abandon my project of translations of his poetry. I went against the grain of his advice and am pleased that I did the translations and published them. Despite the fact that Tychyna’s poetry is complicated, a western reader now has the opportunity to read him in English and get a sense of his poetry. I had a great amount of satisfaction translating the poetry of Viktor Neborak. There is an incredible amount of linguistic complexity in his book The Flying Head, and a translator must at least try to convey the essence of these kinds of complicated avant-garde poetic works. I was also very pleased to hear from a school teacher from the Donetsk reigion, who told me that she was using my Lina Kostenko translations to help teach her students English. That was an unintended positive consequence of my efforts in translation. - If you were completely free to choose, which book or books, whose works would you translate? - ??? At the moment I’m collecting and translating an anthology of contemporary Ukrainian women writers. I’m continuing my work on translating Taras Bulba. The future will tell which writers I’ll work on, though I already know that I would still like to do a collection of translations of the poetry of Mykola Bazhan. Source: http://levhrytsyuk.blogspot.ch/

* * *

- Як Ви стали перекладачем? - Я почав перекладати в університетські роки, коли ще був студентом. Тоді я саме слухав курси російської мови і мої професори (з-поміж яких Вєра Борковец із Чехії) давали мені завдання перекладати декотрі вірші. Тож я перекладав Ахматову, Блока, Мандельштама, Пастернака та інших. Перші мої надруковані переклади з’явилися у літературному журналі «Гіперіон» у 1976-му році. За українські переклади я взявся в аспірантурі у Колумбійському університеті. Я три рази одержав нагороду в університеті за мої переклади російских поетів. А там неабияк підтримав мої зусилля в ділянці перекладу професор Роберт Магвайр. Він сам був перекладачем польської поезії (а також Андрєя Бєлого та Гоголя). Богдан Бойчук, Василь Барка, Ася Гумецька та Іван Фізер, всі підтримували мене, коли я почав займатися перекладами українських авторів. До цієї справи мало хто брався, та ще й Юрій Луцький перестав перекладати через свій вік, от тоді я і вирішив серйозно взятися за справу. Моя перша книжка – переклади Ліни Костенко – вийшла 1990-го року у видавництві Garland Publishers у Нью-Йорку. Мене тоді дуже підтримав Іван Фізер. - З якої мови (мов) Ви перекладаєте і на яку (які)? Як сталося так, що Ви обрали саме цю мову (мови)? - Перекладаю з української, російської та румунської. Власне російська – мій фах, українська – рідна мова моїх батьків. Із румунської почав перекладати завдяки знайомству та спілкуванню із румунською поетесою Ліліаною Урсу, яка двічі приїздила за програмою Фулбрайт до мого університету Пеннстейт. - Розкажіть трішки, як Ви підходите до роботи, перекладаючи роман, збірку новел, збірку віршів. Що спільного? Що відмінного? Які кроки Ви зазвичай здійснюєте? - Завжди намагаюсь триматися близько до тексту оригіналу. Переклад поезії більше потребує слуху. У перекладі поезії треба зберігати звукобудову (чи то «звукоквінтесенцію») оригіналу, а також те, що я називаю органічним ритмом. Приміром, суть вірша Наталки Білоцерківець «Саксофоніст» не можна перекласти без цієї звукобудови. Я старався це передати. Натомість проза більше вимагає логіки, хоча часто трапляється і поетична проза, як-от у Юрка Андруховича. Звісно, поезія також вимагає логіки, але тут важливішу роль відіграють інші елементи, такі як метафори, синтаксис, ритм, рими тощо. Зазвичай я швидко роблю перший варіант або на папері, або просто на комп’ютері. Коли перекладаю поезію, часто читаю оригінал вголос, щоб увійти в мелодію та світ тієї поезії. Тоді полишаю переклад на декотрий час, аби відійти від нього. Вертаюсь до моїх перекладів часто і потрошки правлю. Часом пересилаю друзям на перевірку. Перекладаючи з російської, я співпрацюю із моїм колегою із університету Бакнелл Славою Ястремським. Так, ми разом переклали Марину Цвєтаєву, Ігоря Клєха, Ольгу Сєдакову та інших. До речі, зараз ми працюємо над перекладом першого видання «Тараса Бульби» 1835-го року, що його західний світ взагалі не знає. Дві голови із чотирма очима й вухами більше ловлять, аніж лише одна. До слова, ми надзвичайно гармонійно співпрацюємо вже довший час. Втім, коли перекладаю із української, співпрацюю із різними авторами. Дуже приємно мені працювалося із Ольгою Лучук. Ми з нею зробили антологію української поезії ХХ століття «100 років юності», а також «Літаючу голову» Віктора Неборака. Ольга дуже ретельно працює і добре розуміє обидві мови й, окрім того, різноманітні літературні традиції. Нещодавно колишня моя аспірантка Ольга Титаренко також дуже допомогла мені із моїми перекладами Богдана Ігоря Антонича, Тані Малярчук та Марії Матіос. Давніше Оксана Тацяк мені перевірила переклади Юрія Винничука. Я завжди вдячний за співпрацю із такими добрими та компетентними людьми. Всі вони, до речі, львів’янки, бо я часто приїжджаю до Львова. Я також вдячний Мирославі Приході з видавницва «Літопис», де Михайло Комарницький директор, за її ретельну редакторську роботу над моїми двомовними виданням. - Як Ви отримуєте замовлення? З Вами сконтактовуються видавництва? Чи як це відбувається? - Буває по-різному. Переважно я сам вирішую, що хочу перекласти, і пропоную проект видавцеві. Треба мати або готовий проект, або велику частину рукопису. Я мушу бути захоплений твором, аби його перекласти. Коли вперше читав «Перверзію» Андруховича, вже від перших сторінок я знав, що мені треба його перекласти, а відтак сконтактувався із автором. Раніше я довший час був захоплений поезією Павла Тичини, Ліни Костенко та Максима Рильського, тож зробив переклади кожного із цих авторів. Часом видавництва, літературні агенти або самі автори звертаються до мене. Якщо проект мене цікавить, беруся за роботу. Так, наприклад, мені запропонували перекласти оповідання Сергія Лук’яненка «От судьбы» для антології європейської фантастики – і я погодився, бо твір був цікавим. Так само було із оповіданням Єлєни Арсєньєвої «Береза, белая лисица», що з’явилося в тому самому виданні фантастики. Нещодавно мене попросили перекласти інший твір Лук’яненка «Полуденний фокстрот» для антології про вампірів “By Blood We Live”, що саме вийшла друком (з-поміж видатних письменників там присутні Стівен Кінг, Енн Райс та інші). Якось, до мене зверталися, аби я переклав другу книжку віршів Ліни Костенко, бо в той час її саме пропонували на Нобеля. І я, звісно, погодився задля української справи, але й тому, що шанував її твори. Колись давно, як я ще був в аспірантурі, мені пропонували перекласти збірку віршів Василя Стуса. Я відмовився з однієї простої причини – на тому етапі своєї кар’єри я не був готовий до такої складної лірики. - Що Вас найбільше приваблює в перекладацькому фаху, які його переваги? Недоліки? - Передовсім зауважу, що я не вважаю перекладацьку роботу своїм єдиним фахом. Я не обмежений тільки ним, адже я й сам пишу вірші, пісні, прозу (роман «Сім знаків Лева»), статті тощо. Трошки малюю. Для мене це все – творча робота, і вона приваблювала мене ціле моє юнацьке і зріле життя. Оскільки я викладаю, мій університет розцінює мої перекладацькі роботи як наукову працю. Я завжди пишу вступи для кожної книги перекладів, а також додаю пояснювальні примітки для читачів. Біда (бодай маленька) в тім, що із точки зору фінансів, перекладач художніх творів рідко може заробляти досить, щоб із того нормально жити. Але я маю свою університетську працю, яка мені дозволяє працювати над перекладами. Перекладач художніх творів займається перекладом не задля грошей, а задля задоволення і ширшої справи. - Чи є сенс ставити запитання авторові твору, який Ви саме перекладаєте? - Абсолютно. Коли автор згідний на це, то запитання ставити треба. Я виріс в культурному середовищі не в Україні, а в діаспорі. Деякі українські реалії на відстані мені не були доступні, аж доки я не поїхав до України сам. Декотрі автори з великою охотою відповідають на мої запитання, але не всі. Наприклад, Ліна Костенко ані разу не відповіла (вона жінка із особливим характером). Є автори дуже прихильні. Найбільше можу відзначити Юрка Андруховича за його довжелезні відповіді на мої запитання в роботі над перекладом «Перверзії». Він заслужив нагороду за його терплячість і за його увагу до моїх запитань. Гадаю, треба колись зібрати докупи наші імейли і надрукувати книжку, бо в них – перекладацька і творча майстерня. Додам також, що майже всі сучасні автори, яких я перекладаю, готові відповідати на мої питання і без питань. - Який досвід, які знання та якості особливо важливі для перекладача художньої літератури? - Обов’язково треба багато читати. Мати любов до слова і до словесности. Словники – одна річ. Я маю у своїй бібліотеці усі найважливіші словники (включно із тлумачними) для перекладача. У західних словниках бракує сучасних слів, в українських словниках, виданих в Україні, бракує старих та діалектичних (приміром, галицьких) слів. Словники в Інтернеті (як multitran.ru) та електронні (як Abbylingvo) полегшують справу, з ними можна швидше працювати. Кожен перекладач повинен практикувати, виробляти свій смак і свою інтуїцію. Інтуїція, підкріплена досвідом, є найважливіша. Теоретики перекладознавства переважно не перекладають, а відтак їхній практичний досвід обмежений. Краще не бути рабом якихось теорій, але треба виробляти власні принципи і підходи до роботи. Обов’язково слід досконало знати культуру, історію, літературу і власне лексику тої мови, з якої перекладаєш. Водночас необхідно глибоко розуміти ті самі елементи у своїй рідній мові та культурі. Адже мови й традиції не збігаються. Тому треба добре знати ті моменти розбіжности і вміти їх передати. - Чи існує який-небудь виконаний Вами переклад, що особливо врізався Вам у пам'ять? Розкажіть трішки про нього, будь ласка. - Жодний переклад не є досконалим. Приємніше було мені працювати над «Перверзією», бо там стільки цікавих проблем для перекладача (і мовних, і культурних). Про це я пишу у своїй статті “Translating a Novel’s Novelty: Yuri Andrukhovych’s Novel Perverzion in English”, яку надрукували у журналі Yale Journal of Criticism. Велике задоволення отримую, коли в мене виходить природна поезія англійською в моїх перекладах (зокрема у декотрих моїх перекладах Ліни Костенко, Василя Симоненка, Аттили Могильного та інших). Часом лучиш у точку, а часом (може, і частіше) – ні. Колись один діаспорний літературознавець мені написав, що неможливо перекласти поезію Тичини і що я повинен полишити свій проект. Я пішов проти течії його поради і задоволений тим, що зробив і надрукував книгу. Попри те, що поезія Тичини складна, бодай західний читач тепер має можливість читати його англійською. Велику приємність мав, перекладаючи Віктора Неборака. Страх багато мовних складностей у його «Літаючій голові», але перекладач має бодай старатися передати такі складні твори. Мені також було надзвичайно приємно чути від однієї викладачки із донецької області, що вона використовує мої переклади Ліни Костенко для їхніх студентів у вивченні англійської мови. - Якби Ви були цілком вільні обирати - яку книжку, які книжки, творчість якого автора Ви перекладали б? - ??? Тепер збираю і перекладаю збірку сучасних українських жінок-письменниць. Продовжую працю над «Бульбою». Майбутнє скаже, над ким і чим буду працювати (хоча вже знаю, що хочу зробити збірку перекладів поезії Бажана)…

(Михайло Найдан вдячний Марії Титаренко за відредагування його відповідей.) За матеріалами: http://levhrytsyuk.blogspot.ch/

Read: Recent comments for the page

«Interview with a Translator: Michael Naydan»:

Refresh comments list

Total amount of comments: 0 + Leave a comment

|

|