|

The first martyr of the Revolution of Dignity was Serhiy Nigoyan, a Ukrainian of Armenian descent. He was shot to death on January 22, 2014, by the special police forces known as “Berkut” (“Golden Eagle”). Nigoyan was 20. During protests a month earlier, he had been filmed on Independence Square reciting a passage from Shevchenko’s poem “The Caucasus,” lines that continue to inspire Ukrainians today: Fight — and you’ll be victorious, In Nigoyan’s moving recitation of Shevchenko’s lines and his violent death soon after, the Caucasus and Ukraine were again joined against Russian aggression and oppression. “The Caucasus,” written in 1845, is Shevchenko’s portrait of the nineteenth-century Russian imperial frontier, where Russia waged a bloody war for nearly fifty years. The poem is the most poignant invective against Russian imperialism and colonialism to be found in any language. In this complex and revolutionary poetic work, Shevchenko establishes the connection between Russia’s brutal conquest of the Caucasus in the name of progress, civilization, and security, on the one hand, and on the other, the oppression, rapacity, and depravity of an imperial system based on serfdom, corruption, and hypocrisy perpetrated throughout the territories of the Russian Empire. The insight and power of Shevchenko’s poetry are no less remarkable and relevant today, as Putin’s Russia attacks Ukraine’s sovereignty and the freedom, human dignity, and cultural identity of its people. No other poem captures the force of this historical moment as poignantly as “The Caucasus.” This work, written nearly 180 years ago, is uncannily, eerily prophetic, and, for the Ukrainian people fighting for their lives and for the very existence of their country today, remarkably affirming.

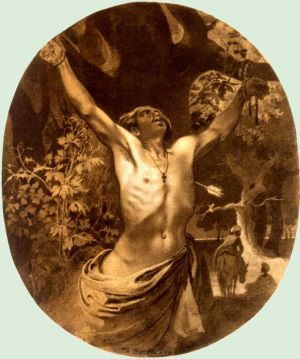

Yet Shevchenko, despite his genius and acknowledged greatness in the Ukrainian literary tradition, is largely unknown outside of it, and his works have not received the attention they deserve. The neglect of this important literary voice, and, by extension, the entire culture that stands behind him, is a reflection of the dominance of Russian colonializing narratives in the West. In other words, we have fostered the so-called “great” Russian literary tradition to the point that it dominates the Eastern European literary canon and cultural discourse, with the result that Ukrainian and other non-Russian literary voices have been silenced. Putin’s unprovoked war of genocidal aggression and terror illuminates the profound dangers and injustices inherent in this silencing. When Putin claims that Ukrainian culture has no basis for existence as a pretext for unleashing mass destruction on a scale unseen since the Second World War, it becomes clear that the cultural sphere is inseparable from the political, and that literature matters to people’s real lives. Shevchenko’s brilliant, ground-breaking critique of great power imperialism are revelatory, and no introduction to his work is more fitting than his poem “The Caucasus.” At the time of its writing, Shevchenko took on and dismantled the conventional image of the Caucasus as found in Russian literature in the works of Pushkin, Lermontov, and Tolstoy, who wrote about the Caucasus through the lofty imperial lens as a place of sublime grandeur and beauty. Shevchenko wrote the poem after his friend Iakiv de Balmen, a fellow visual artist and writer, was killed in a battle between Russian troops and Chechens. Remarkably, Shevchenko’s poem continues to have the power to eviscerate arguments that cast Russia’s current military conquest as a “civilizing” project and deny moral responsibility for the resulting violence and suffering. “The Caucasus” is remarkably complex in its shifting rhythms and emotional registers. Moving from intimate, lyrical rumination, to grievances against divine and political authority, it employs biting political sarcasm and elevated prophetic ardor. The opening passage evokes the image of the mythical rebel Prometheus, eternally suffering at the claws of a ruler-sent eagle, yet indestructible in his vitality — a symbol of the undying pursuit of goodness, liberty, and humanity. In the sections that follow, the poet turns to the horrors of war and oppression and challenges both God and the world order. Mimicking the “superior” voice of the colonizer, Shevchenko exposes the brutality, avarice, and hypocrisy of Russian imperialism.

Who was this man who saw and expressed what others could not, and why is his position in Ukrainian literature so unique?

Taras Shevchenko (March 9, 1814-March 10, 1861) was born a serf in a village in the Kyiv region and was orphaned when he was eleven years old. As a boy, he was an agricultural worker and engaged in menial labor. A deacon at his church taught him to read and write. From his early years, he showed a passion for drawing, learning from local icon-painters and doodling whenever the opportunity presented itself. At the age of fourteen, he became the personal servant of the man who owned him. While accompanying his master on a trip to St. Petersburg, Shevchenko became acquainted with artists at the Imperial Academy. Recognizing his talent, the artists launched a fundraising campaign, and in 1838, he was bought out of serfdom from his owner for 2,500 rubles. Shevchenko enrolled in the Imperial Academy of the Arts and his career as an artist progressed. All the while, he found emotional and creative refuge in poetry. His first collection, Kobzar (Blind Bard), appeared in St. Petersburg in 1840 and was noticed by the critics and enthusiastically received by the Ukrainian intelligentsia and educated gentry. In the 1840s, while traveling in Ukraine with a plan to draw a series of landscapes and historical sites, Shevchenko befriended members of the Ukrainian intelligentsia. This circle of friends became the basis of the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius, an organization that supported a federalist union of Slavic peoples, the emancipation of the serfs, and pondered plans for reviving Ukrainian cultural life. During this time, Shevchenko wrote some of his most forceful and radical poems, including “The Caucasus,” which were gathered in the collection "Try lita" (Three Years). In 1847, the members of the Brotherhood were arrested and taken to a St. Petersburg prison and interrogated, their papers confiscated and closely examined by the police. Of these papers, Shevchenko’s poetry proved the most grievous, and he received the harshest punishment: exile to the steppes of Kazakhstan, where he was conscripted as a rank-and-file soldier into the imperial army for a term of 25 years. Russian Tsar Nicholas I personally forbade Shevchenko from writing and drawing. Despite the prohibition, Shevchenko continued to write in secret, in small self-made notebooks that he hid in a boot leg. Only after the death of Nicholas I did the appeals by various high-positioned supporters to free Shevchenko meet with success. Released in 1857, he revived his skills as a graphic artist. He continued to write until his death in 1861-a month short of the imperial decree abolishing serfdom in the Russian Empire. The poems that comprise the album “Three Years” were prohibited in the Russian Empire and were circulated in manuscript form clandestinely. Many were first published in 1857 in a collection of political verses by Pushkin and Shevchenko that appeared in Leipzig, beyond the purview of the Russian censorship and secret police. Among these works is “The Caucasus”. While there have been previous attempts to render the poem in English (by Vera Rich, John Weir, Peter Fedynsky), it remained for Alyssa Dinega Gillespie to convey the full emotional, poetic, and polemical impact of the work. Shevchenko never visited the Caucasus, and yet his poem was unprecedented in its exposure of the brutality, exploitation, oppression, and duplicity of colonizers who perpetrate genocidal violence there under the guise of enlightenment, modernization, and religious faith. His insights were born of his experience as a Ukrainian poet, former serf, artist, self-educated thinker, and critic. Shevchenko’s uncompromising cry for an unmasking and condemnation of imperial “beneficence” continues to inspire. Ultimately, the poet presents a vision of a future in which justice may prevail — over the imperial eagle, the Berkut police, and authoritarian rulers who think they can crush the quest for human dignity and freedom. Taras Koznarsky, University of Toronto

Source: https://lithub.

Please read:

Translated by Alyssa Dinega Gillespie.

Recent comments for the page

«Associate Professor at the University of Toronto Taras Koznarsky — about 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine and Taras Shevchenko’s poem "Caucasus" translated by Alyssa Dinega Gillespie»:

Refresh comments list

Total amount of comments: 0 + Leave a comment

|

|

In 2014, Russia responded to the protests in Ukraine known as the Revolution of Dignity, which drove out corrupt President Yanukovych, by annexing Crimea and destabilizing eastern Ukraine. These events overlapped with the bicentennial anniversary of the birth of Taras Shevchenko, the great Ukrainian poet of the Romantic era. During the dramatic, euphoric and tragic days on the barricades at Independence Square, Ukrainians recited Shevchenko’s poetry, and street art featuring his image—stylized as Superman, a street protester, Elvis Presley, and Buddha—was a source of both humor and strength for Ukrainian citizens fighting to safeguard their country’s independence and European-oriented future.

In 2014, Russia responded to the protests in Ukraine known as the Revolution of Dignity, which drove out corrupt President Yanukovych, by annexing Crimea and destabilizing eastern Ukraine. These events overlapped with the bicentennial anniversary of the birth of Taras Shevchenko, the great Ukrainian poet of the Romantic era. During the dramatic, euphoric and tragic days on the barricades at Independence Square, Ukrainians recited Shevchenko’s poetry, and street art featuring his image—stylized as Superman, a street protester, Elvis Presley, and Buddha—was a source of both humor and strength for Ukrainian citizens fighting to safeguard their country’s independence and European-oriented future.