Reflections on Taras Shevchenko by an American in Ukraine

For the habitual voyager, arriving in a new country is the ultimate traveling experience. The sights and smells, the vistas of fresh landscapes, the architecture, all officially announce an adventure has begun. Diplomats may be some of the best explorers in history, from Ibn Battuta, to Machiavelli, and Benjamin Franklin. They leave their homeland in the service of their leaders, and depart with a profound understanding of other citizens and cultures.

I arrived in Ukraine just in time for the New Year. Bundled against the cold, I began my exploration of the city. With encouragement from colleagues at U.S. Embassy Kyiv, I will blog about my discovery of Kyiv and Ukraine.

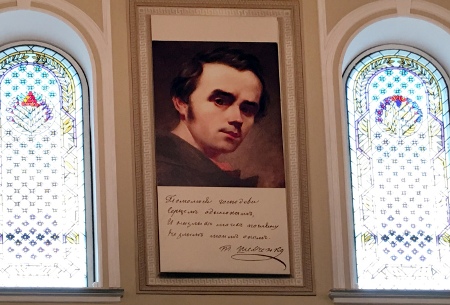

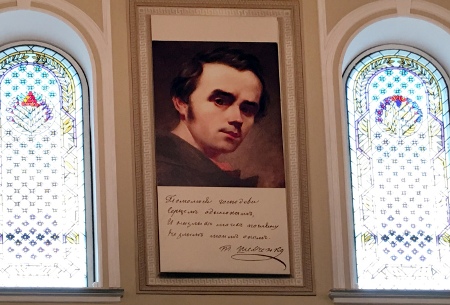

On March 9, Ukrainians celebrated the 203rd Anniversary of the birth of Taras Shevchenko, the beloved poet, writer and civil activist who is often called the father of Ukrainian literature. To mark the occasion, U.S. Embassy diplomats recorded some of Shevchenko’s verses. With an Embassy group that included Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch and her mother, Miss Nadia, I toured the Shevchenko Museum to discover more.

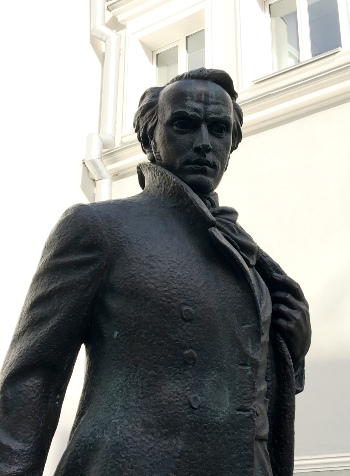

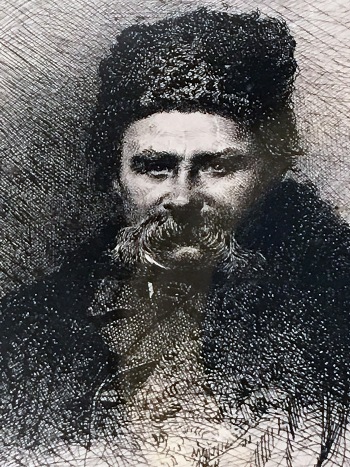

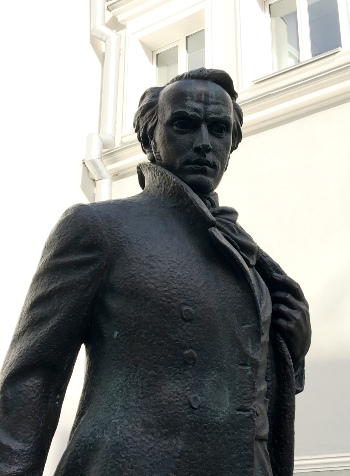

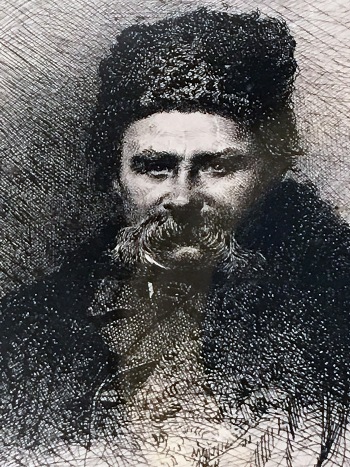

The Taras Shevchenko Museum is located in Shevchenko’s beloved Kyiv in a mansion formerly owned by a wealthy sugar magnate. This juxtaposition of housing the most comprehensive collection of artifacts, paintings and memorabilia from Shevchenko’s life, surrounded by such opulence is ironic and poignant. For Ukrainians, Shevchenko is the premiere national hero. Son of a serf, at once a novelist and a painter, a poet and a prisoner, Shevchenko was a celebrity and political figure, who finally returned home to the area near the town of Kaniv, to be buried after his death. To a new generation of Ukrainians, those born after the Soviet era, raised with a unique identity, and who came of age in the era of EuroMaidan, Shevchenko’s dream of Ukrainian freedom resonates with renewed vigor. The museum provides an opportunity for foreigners and natives alike to make his acquaintance and to draw lessons from his writings on the past and future of Ukraine.

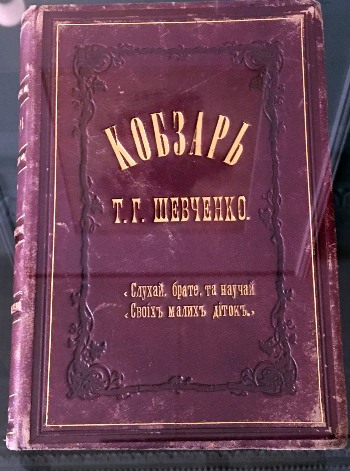

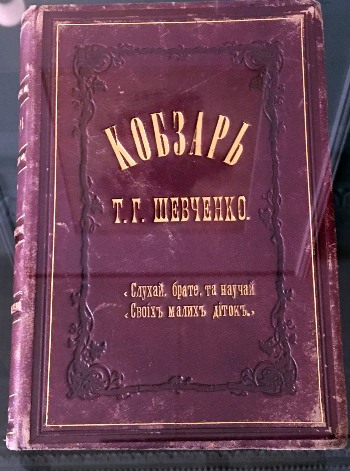

The museum is housed in one of the many beautiful buildings that grace the cobblestoned streets in the old city. It opens on to a modern glass atrium, with ample room for a collection of modern art. Progressing up the marble staircase to the second floor, I walked through room after room adorned with paintings, drawings, and books. I learned of the Cossack history of Ukraine, and then was led step by step through the various stages of Shevchenko’s life. Shevchenko’s life story is well known in Ukraine. Born in 1814, Shevchenko grew up in poverty, was orphaned at the age of 11, and yet managed to acquire an education working as an apprentice to a teacher and deacon. His early life was dictated by the whims of his masters, yet his time in Vilnius was productive in providing him with an artist’s training. His subsequent travel with his master to the Russian capital of St. Petersburg changed his life. Shevchenko was accepted to the Imperial Academy of Arts, and was able to study painting. More importantly for the history of Ukrainian literature, he began to write poetry. He also became acquainted with other Ukrainians diaspora artists, one who bought him his freedom in 1838. In 1840, his first book of poetry, “Kobzar” was published. This was the beginning of a new chapter, one that would bring him into conflict with the Russian Imperial family and others in the ruling class whose patronage he needed to survive. Subsequently he penned poems in Ukrainian, where he was critical of the system of serfdom and of the regime of Tsar Nicholas I. Shevchenko’s last prison sentence was serving six years at a penal colony in Novopetrovsk. On his release, he returned to St. Petersburg where he continued writing until his death at the age of 47 on March 10, 1861, seven days before the emancipation of the serfs.

But what exactly did the Russian Empire fear? I looked for those verses that resonated then as now, to understand the Ukrainian identity and their heart that longs for freedom.

When I am dead, bury me

In my beloved Ukraine,

My tomb upon a grave mound high

Amid the spreading plain,

So that the fields, the boundless steppes,

The Dnieper’s plunging shore

My eyes could see, my ears could hear

The mighty river roar.

When from Ukraine the Dnieper bears

Into the deep blue sea

The blood of foes … then will I leave

These hills and fertile fields —

I’ll leave them all and fly away

To the abode of God,

And then I’ll pray …. But till that day

I nothing know of God.

Oh bury me, then rise ye up

And break your heavy chains

And water with the tyrants’ blood

The freedom you have gained.

And in the great new family,

The family of the free,

With softly spoken, kindly word

Remember also me.

Taras Shevchenko

1845, Pereiaslav

Translated by John Weir

Pauletta Walsh, Assistant Information Officer, U.S. Embassy Kyiv

Source: https://usembassykyiv.wordpress.com/