|

Shevchenko for all ages

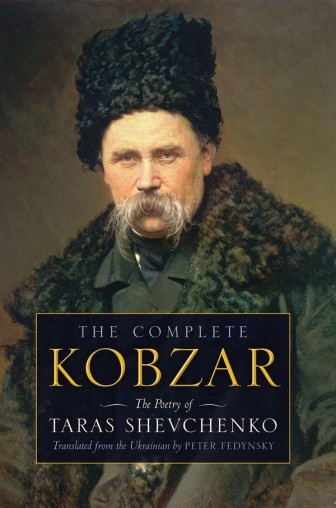

The Complete Kobzar: The Poetry of Taras Shevchenko, translated from the Ukrainian by Peter Fedynsky. London: Glagoslav Publications, 2013. 450 pp., paperback and hard-cover.

Over the years I have come across many English translations of the poetry of Taras Shevchenko, Ukraine’s poet laureate. Books by C.H. Andrusyshen and Watson Kirkconnell as well as Vera Rich come immediately to mind. John Weir, E.L Voynich, Clarence A. Manning Michael M. Naydan and Honore Ewach have also contributed their translations. In 1989, the Ukrainian Fraternal Association published Andrew Gregorovich’s bibliography of English-language books on Shevchenko, printed between 1911 and 1998. There were more than 500 listings. Upon learning of the English-language publication of “The Complete Kobzar” by Peter Fedynsky, one could reasonably ask: do we really need another English language translation of Shevchenko’s poems? The answer is a resounding yes! For two reasons. The first is that this is the first English translation of the “Kobzar” in its entirety. The second reason is articulated by Prof. Michael M. Naydan in his introduction (“A Kobzar for a New Millennium”) to the book: “to convey the poet’s verse in a modern English idiom that could be easily understood by readers of today.” I’ve been attending Shevchenko commemorations since about the age of 6; and yet, as much as I hate to admit it, I have never read Taras Shevchenko’s “Kobzar” in its entirety, either in Ukrainian or in English. I was familiar, of course, with excerpts such as: When I die, then bury me Atop a mound Amid the steppe’s expanse In my beloved Ukraine… What Ukrainian isn’t aware of those immortal words? But my appreciation for the marvelously fertile writing of Ukraine’s poet laureate was largely superficial. Shame on me! Reading Mr. Fedynsky’s “The Complete Kobzar” helped change all that. I am now more at home with the genius of Shevchenko and his enormous contribution to Ukraine and the world. Mr. Fedynsky’s contribution to my understanding is enormous; at the same time, I am aware that I still have a long way to go. A re-reading of the “Kobzar” is called for if I am ever to become more “Shevchenko aware.” What struck me from my initial reading of Mr. Fedynsky’s translations of the “Kobzar” was the rich imagery. Consider: The mighty Dnipr’ roars and groans An angry wind resounds, It bends tall willows to the ground, It raises waves like mountains. Or how about this: In the grove a wind Bends the willow and poplar It breaks the oak and tumbles Tumbleweeds across the field. Or this: Two lofty poplars grow Beside a grove Amid an open field On the apex of a mound Each leaning on the other. Or this: Raging wind, O raging wind! You talk with the seas Awaken it, and play with it, Ask the azure sea. These verses were visual; they made me feel as if I was there. Literally. Taras Shevchenko often described his own torment as an orphan: Life on earth is tough and trying For an orphan without kin, There is no place to rest. Might as well just leap From a mountain into water. Shevchenko “depicts orphans in various contexts,” writes Mr. Fedynsky in his introduction, “including the parents in the poem Kateryna, who are ‘orphaned in old age,’ and the river Dnipro that would be ‘orphaned with the sacred mountains.’ The ill-fated lovers in his first poem, ‘Mad Maiden,’ are both orphans. In the long poem ‘The Haidamaks,’ the murder of the Sexton leaves his daughter orphaned… The kobzar minstrel is an orphan in the poem ‘The Rambler,’ so too is Stepan in ‘The Blind Man.’” Shevchenko wrote about thoughts that seemed to consume him: My thoughts, my thoughts, Troubled is my life with you! Why’ve you stood on paper In a sad array?… Shevchenko is at his best, however, when writing about Ukraine’s grim history. In “Holy Day in Chyhyryn” we read: Hetmans, hetmans, if only you’d arise, Arise to look upon Chyhyryn You built and where you ruled! How hard you’d cry, for you’d not Recognize the paltry ruins Of Kozaks’ bygone glory. In “The Plundered Mound” Shevchenko writes: Placid earth, O my dear land, O my dear Ukraine, Why have you been plundered? What is it, mama that you’re dying for? Before the break of dawn, Did you not teach tradition… In “Hamaliya,” we read: O dear God of our Ukraine! Don’t allow free Kozaks To perish fettered in an alien land, It’s shameful here, it’s shameful there- To rise up from a foreign coffin, To attend to your righteous judgment, To come with hands in iron, To stand with all in chains as Kozaks…” Convinced that Taras Shevchenko’s “Kobzar” was for all generations, even those who neither speak nor read Ukrainian, I asked one of my granddaughters, 13-year-old Natalie Kuropas, to review the Fedynsky book. She came up with the following commentary. * * * When asked to read “The Complete Kobzar,” I was hesitant at first. Hearing that it was translated by an American-born Ukrainian had me a bit skeptical. I wasn’t sure if the product would make sense in the end, or if the emotion would make the journey through translation. But in reading it, I soon realized that my doubts were in vain. The translation, as well as the poetry, was proven to be beautiful and clear. The message in each poem was obvious and touching all the same. There were also definitions for the words that didn’t have a straightforward definition in English and were left in Ukrainian, which I really appreciated. Even if you do not know Ukrainian, you can still easily read this book and fully understand the poetry. I also particularly enjoyed Shevchenko’s drawings that were included in the book as well. Many of Shevchenko’s poems illustrate sorrowful tales that show the thoughts and fears of the time. Some poems create a story of a girl who is shamed for losing her lover and is shunned by her family. Others portray the lives of those without purpose or lives that are ruined. The downcast truth of reality is evident in Shevchenko’s poetry and reminds us to appreciate what we have and how important tradition was when he was alive. We often take our blessings for granted, and this book makes you remember what you do have. One of my favorite poems in the book is “Kateryna,” a poem Shevchenko wrote to Vasilii Andreyevich Zhukovsky, a fellow poet at the time. The poem tells of a young girl who fell in love with a Muscovite soldier, despite everyone’s warnings. Her friends tell her to never fall in love with a Muscovite because he will love her jokingly and leave her jokingly. Kateryna falls for him anyway. They spend a wonderful time together, but then her lover must leave for war, and she is abandoned. She becomes pregnant and gives birth to a son, immediately ashamed. In the eyes of the townsfolk, she is no longer human for giving birth, with the father nowhere to be seen and without being married. Her parents are ashamed. They tell the daughter to leave, practically disowning her, saying that if she truly loved the man she was with, she would go after him. And if he really loved her, he would go come back to her. Kateryna has no choice but to accept and leave the shame she carried behind her. She goes off with her child to find her lover. Soon the winter months come, and she is still trying to find him. Her clothes are torn and filthy, and she is struggling to find the motivation to go on. Eventually she stops caring about her own life and only wants to keep her baby alive. The poem goes on in a fascinating way that truly grips the heart. You can feel Kateryna’s pain and despair as she travels with her child. The ending was surprising and heart-wrenching, and all the emotions of the original poem are truly there. I was really impressed with the way it was written, so beautiful and elegant, yet sorrowful and almost frightening. “The Complete Kobzar” was a joy to read. I felt as if the poems hadn’t been translated at all and I was reading what Taras Shevchenko himself had written so long ago. Although the book might be slightly intimidating at first glance, it is easy to fall in love with the writing and the accompanying drawings. The translations of the poems are beautiful and hold the same purpose and meaning that Shevchenko was trying to convey. I would certainly recommend this to anyone who wants to go on a rollercoaster of emotions with each poem, as its meaning reveals itself with passion and heart.

** Myron B. Kuropas, Ph.D., was born in Chicago to activist Ukrainian parents and received all three of his degrees in the city: Loyola University (bachelor of science), Roosevelt University (master of arts), and the University of Chicago (doctor of philosophy). He is the author of two major books: The Ukrainian Americans: Roots and Aspirations, 1884-1954 and Ukrainian-American Citadel: The First Hundred Years of the Ukrainian National Association. He has been active in many Ukrainian organizations, including the Ukrainian National Association and the Organization for the Rebirth of Ukraine. During the administration of Pres. Gerald R. Ford, he served as a special assistant for ethnic affairs. In 2004, he was awarded the coveted Shevchenko Freedom Award for his service to the Ukrainian community in America. Dr. Kuropas is currently an adjunct professor at Northern Illinois University.

Source: http://www.ukrweekly.com/, https://www.arcadiapublishing.com/ Recent comments for the page

«"Taras Shevchenko for all ages" by Myron B. Kurops (аbout the Poetry of Taras Shevchenko, translated from the Ukrainian by Peter Fedynsky)»:

Refresh comments list

Total amount of comments: 0 + Leave a comment

|

|